Jock Zonfrillo’s all-consuming quest for an Australian cuisine

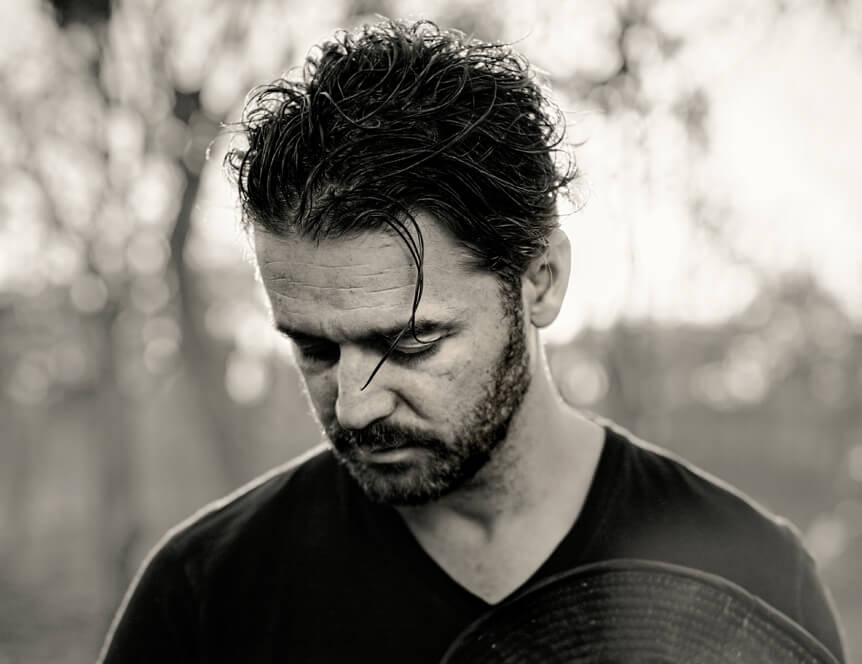

Jock Zonfrillo looks as though he shouldn’t know how to cook. Even in his whites and apron, even hailing guests at the restaurant door, even reciting for you the facts of a given dish; his tattoos, his unruly hair, his gift for profanity suggest a punkish hipster, not the chef-owner of a fine-dining establishment in central Adelaide. And not – especially not – the leader of a culinary expedition whose modest objective is the realisation of a wholly new cuisine.

One of his tattoos is a skull-and-crossbones nestled among the Scottish flag and his children’s names. It’s there to remind him of his motto: “Why join the navy when you can be a pirate?”

There are only six tables at his restaurant Orana and it’s a fixed menu, while downstairs at Street ADL there are communal tables and the menu is fixed to the wall. Jock is in charge of both eateries, but it’s Orana where the lights are dimmed just so, where there’s a sommelier introducing wines to your table, where the restaurant manager clears the plates. And it’s Orana where Jock’s culinary expeditions take flight.

But first, before the culinary expeditions, come the actual expeditions.

Darwin, 3000 kilometres north of Adelaide, and the capital of the Northern Territory, still feels like a remote mining town. There’s dust in the wake of every car and the streets are empty on a Sunday. To get there, you fly over a conveyor belt of open quarries and upturned earth, where Australia’s natural resources boom booms on. But Jock is on the hunt for a very different kind of natural resource.

This part of the Northern Territory is red dirt and bushland cut into generous portions by straight roads that run forever. You can drive all day without having to turn the wheel or even brake, but for the occasional flock of wedge-tailed eagles feasting on roadkill. There are termite mounds that rise taller than a tall person and hiking out here you could easily get lost and never be heard from again.

After four hours of driving, our rented Land Cruiser arrives at a billboard: “Welcome to Nauiyu, Daly River”. Nauiyu is pronounced Noy-oo-yoo.

This is a small town built around its football oval. The homes are single storey and rambling and there are dusty boats parked in the driveways. It’s a tropical place full of palm trees and parrots. Dogs lie like corpses in the shade.

Most Aboriginal communities have a dedicated space for Aboriginal art. When Jock arrives somewhere for the first time, that’s where he goes. He can use the artwork to familiarise himself with the local foodstuffs: paintings of turtles and marron, silkscreen prints of crocodile eggs and barramundi. It’s also where he meets people. Here, at the Merrepen Arts Centre, Jock meets Kieren Karritpul McTaggart, an artist who, a week from today, will win the Youth Prize at the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.

For now, however, he’s just an ordinary bloke. But his mother, who comes and sits with Jock beneath the ceiling fans, is far from ordinary.

Patricia Marrfurra McTaggart has fuzzy hair, bright, floral clothes and large spectacles on the crown of her head. She is quietly spoken and thoughtful. She has books about local plants and animals to her name, as well as dictionaries for the Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri languages. She hunts pigs, ducks, geese and wallabies, and she’s licensed to drive a truck.

It’s Jock’s experience that the person locals turn to for foraging and cooking advice is invariably a female elder. When people show up to ask Patricia questions about bush tucker, they’re usually survivalists and military groups learning how to locate food in the wild, learning how to make traps out of whip vine, how to repel insects with cypress bark. But when Jock tells her why he’s here, she responds with a smile:

“You’ve come to the right person.”

No lack of ingredients

Jock got here as a teenager in the early 1990s. As well as naïve surprise at the dearth of kangaroos hopping down Sydney streets, he felt the sobering surprise that would come to define his professional life.

“It was confusion. And it was a little bit of sheer amazement. How could we be this country with these amazing ingredients, but with no cuisine? It just didn’t make sense to me. I was dumbfounded by it, really. Incensed by the fact that there’s such amazing produce here and no one had really given it the attention it deserves.”

To an average Australian, Orana’s menu reads like something from a Roald Dahl book: frozen green ant sorbet, crocodile and pickled grey mangrove. That, or a list of made-up words: smoked Goolwa cockle, bunya and spruce pine, iceplant and bullrush ash, pandanus mother, vetch pea shoots, fermented lilly pilly.

In fact, your average Australian might have heard of pandanus or lilly pilly, but they wouldn’t know you could eat them. They might have heard of green ants, but they wouldn’t know you could use them instead of lemon to season a dish.

Your average Australian doesn’t know these things and yet, at any given moment, you can look around the dining room and spot your average Australian muffling their orgasms as they reach for another bite.

Jock’s four-wheel-drive follows Patricia’s four-wheel-drive out of town and into the wilderness of greater Daly River. They arrive at a portion of bushland recently burned off by the locals. This is a traditional method of land management that leaves eerie segments of blackened trees and ash that crackles beneath your feet.

Foraging in the wild

Four women emerge from Patricia’s car and scour the ground for tell-tale green sprouts, those that seem indistinguishable from all the other green sprouts but which have such singular attributes as to prompt each of these women to sit cross-legged and hammer the dirt with crowbars.

To their number is added a Scottish chef, mucking in despite the heat of the day. His addition is a surreal image. But in a place as alien as this, surrealism is not difficult to achieve.

The ground is hard like rock and heavy precise strokes are required. These are physically strong women, who dig, dig, dig, and Jock is equal to the task, bringing to bear the right mix of power and delicacy.

The aim is to fully unearth the bush carrot without breaking it. Finally, Patricia’s comes free. She peels it and offers a piece. To eat it raw you chew the fleshy outside and spit out the fibrous core. Jock declares that it tastes like a cross between a potato and a raw chestnut.

“I’ve never had it before,” he says. “I think it’s amazing. Surprising it’s so sweet when the ground here is so dry. Fibrous but juicy at the same time.”

He says that, at Orana, bush carrots could be a stand-alone dish. But the first step will be to break down that tough core. This might be attempted a hundred times, over the course of years, before the Orana team finds the right method and temperature.

Perhaps a long period of braising, or fermentation, or the introduction of an acid or a heavy alkaline to assuage the texture. It’s the same experimentation that happened centuries ago to garlic, coffee, cocoa, olives . . .

Dig, dig, dig, until you unearth the solution. This is what the forging of a cuisine looks like.

Most of the food at Orana grows wild and has to be foraged by Aboriginal communities, by professional foragers, or by Orana’s own kitchen staff. They’re on rotation, each spending a month at a time gathering food in the Adelaide Hills.

“We’ve got a pretty good base knowledge about what’s here, there and everywhere, especially during seasonal change,” says Shannon Fleming, head chef. “So it might be as easy as going for a couple of hours into the hills with my kids. They love it.”

And it’s this proximity to wild food that accounts for Orana’s location. Adelaide provides better access to the rest of the country, to all of the country. Wild produce doesn’t transport well.

The kitchen in Orana is the size of a toolshed and it’s astounding that this should be the laboratory for Jock’s brand of mad-scientist experimentation. And yet the small space can only encourage – enforce – camaraderie among the scientists.

Recently, when Sydney chef Kylie Kwong sought advice from Jock for the creation of a beer flavoured with indigenous ingredients, some of his staff were disappointed that Jock so readily divulged his secrets. But Jock says that this missed the point: the goal is not a great dish nor even a great restaurant, but a gastronomical revolution.

“What I’m trying to do is to connect everybody. The more people get involved, then the more genuine and amazing it will be. If it’s just one guy doing it, it’ll be shit.”

The bush tucker trend

Jock is following Patricia’s Land Cruiser. When they reach the billabong, it’s alive with bugs.

They’re here to find the tuber of the white lily, which drifts beneath the water and tastes like potato if the billabong is clean. Orana already uses these in a black pepper paste served with blue swimmer crab, but Jock hopes that this community will represent a new supplier.

“Whenever we can help a community by paying for it, obviously we will do that. I would sooner buy from a community, over and above anything farmed or mass-produced. And I’m happy to pay a little bit more for it.”

Sometimes these communities are stunned by how much Jock is willing to pay. “There’s a whole financial aspect for them, to help fight for land rights, to help with schooling for the kids, buying textbooks, crayons, pens, pencils. There are a number of medications that are required in communities that they have to pay for. So there’s a huge reason to purchase from a community. But above all else, it’s an act of honesty.

“It’s an act of breaking bread. It’s one step closer to unity, to celebrating this place together. As opposed to them and us, you know?”

It’s easy to imagine that the term “bush tucker” was coined by Jamie Oliver, perhaps while touring Australia. But it has been the name for indigenous food, in white and Aboriginal communities, ever since settlement. In the 1980s, it started to trend, helped by the broadening Australian palate and popular TV programs.

“When bush tucker happened in the 1980s and 1990s, they picked a handful of ingredients and thought, ‘These will be marketable, we can mass-produce them, let’s go.’ And then there was no information given to the marketplace as to what to do with them.”

According to Jock, this meant that consumers did little more than garnish an existing menu, or else they dried out native foods and used them as a meat rub. “And that was supposed to be Australian,” he says.

“Modern Australian” is the closest thing to a national food style, being a minor, local twist on recognisably international dishes.

“It’s fusion, mostly pan-Asian,” Jock says. “Barramundi on a bed of bok choy.”

What he and the Orana crew are consciously developing is a form of cooking that begins with indigenous ingredients and traditional cooking methods, then enhances them with other ingredients, other cooking methods. If pumpkin will improve the dish, they will add pumpkin. There is beetroot and coconut and goat’s cheese in their meals. So it’s not bush tucker, it’s not Modern Australian, it’s not strictly native, but it’s not fusion either.

Jock says, “What’s wrong with calling it Australian?”

All-consuming mission

Jock was born in Glasgow to an Italian father and a Scottish mother.

At the age of 12, he was washing dishes, saving for a push bike. By 21, he was running the kitchen at the Hotel Tresanton in Cornwall. His United Kingdom resumé includes working at The Restaurant Marco Pierre White at the former Hyde Park Hotel, now Mandarin Oriental.

He first came to Australia in the 1990s but settled here in 2000, which is the same year he recovered from his seven-year heroin addiction. You ask if he’s replaced heroin with something else, and he says, “No. Except maybe work.” Which might account for this all-consuming life mission.

The long hours of a dedicated chef are well known, but on top of that has been Jock’s commitment to first-hand experience of these communities. Experiences that can’t be gleaned by phone. Can’t be googled.

Wild ducks, hunted and shot, are beheaded, plucked and gutted. As Jock looks on, Patricia appears to unfold the duck with her hands, removing pieces of bullet as she goes.

“That’s not your normal spatchcock . . .” Jock says.

They’re placed over the coals beside other cargo, a local word for meat. This includes wallaby fillets and bones, and a pot holding wallaby heart and liver, cooking in water.

“We eat everything,” Patricia says. “Eat the brain, the eye, the tongue. Everything.”

The group feasts as the sun sets. The swarm-noise of insects builds like an approaching army. It’s time to leave Daly River. There are hugs, mamaks (goodbyes). Jock promises to come back in October in time for magpie geese.

Driving back to Darwin, Jock can barely contain himself over the spatchcock. His excitement pours out of him like a dam burst. I recorded some of it on my phone. Here is just a fragment:

“. . . the way they’ve done it, the two legs are beside the breast, so you can sit the two legs on the grill, with the breast hanging off so it doesn’t overcook, and the bird cooks evenly. It’s f—ing genius. It’s f—ing genius . . .”

The Orana Foundation is, in part, an incorporation of Jock’s ideals and his hopes for Australian cooking. But it is also intended to address the increasing fragility of Aboriginal culture, a fragility that Patricia and the Nauiyu people are battling against with every fire, every hunt.

“It’s a race against time,” Jock says. “Across Australia, there’s a large group of elders that will pass away in the next five years. We want to capture that information somehow. It should be available to their people. If we can do that, it’s as much for them as for us.”

The foundation will be a hub for communities, researchers and chefs; to share knowledge, to preserve it and to develop it in perpetuity. The Orana Foundation, Jock says, will make native food, and the body of research surrounding it, available to all.

“I know that if I do this properly, many people will start looking at these ingredients with a fresh pair of eyes. Chefs who are much better cooks than I am will make even better things, make even more connections, start visiting these communities and making new dishes. And eventually, you’ll have a really amazing, unique cuisine in this country.”

Jock says, “You know, I’m not going to bring this journey to a point and say, ‘Here’s Australian cuisine’. That’s going to happen long after I’m gone.

“And that’s really what the foundation is all about, to make sure that happens, whether I’m here or not.”

He says, “This will continue long after I’m dead.”

Original Article: Financial Review